NB: See also the second part of this interview, “Truth or Consequences: Bill Jersey on the End of Evangelicalism (Part 2),” published January 10, 2018, and a new interview with Bill, “America Against Itself: A Time for Burning (Again) – published July 7, 2020.

********

In continuation of the conversation about religion, race, and Trump that I began some weeks ago with the great Catholic thinker and writer James Carroll (“The Invention of Whiteness” and “The Disadvantages of Decency“), I recently sat down with the legendary documentary filmmaker Bill Jersey, whose perspective on the issue is both rare and highly personal.

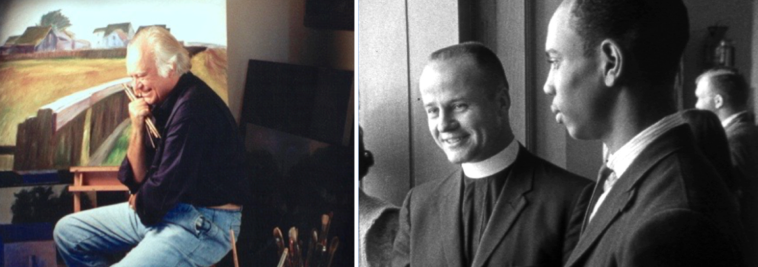

One of the pioneers of the cinema verité movement and a winner of the Peabody, Dupont-Columbia, and two Emmy Awards among many others, Jersey is one of the most accomplished documentarians of the modern era. At 91 years of age, Bill’s other honors include two Oscar nominations, including one for A Time for Burning (pictured above), his searing 1966 study of a Lutheran church in Omaha, Nebraska wrenched over racial integration, which has found a disturbing new relevance in the Trump era.

Over the course of his long career, Jersey has been strongly identified with that sort of deeply humanistic, Berkeley-based brand of social justice-oriented filmmaking. But Bill was raised in—as he calls it—a “Bible-believing” fundamentalist Christian family, giving him a unique frame of reference on that community, especially in our current, perilous, logic-defying times. (See end of post for Bill’s full bio.)

TESTIFY

Contrary to popular myth, religion has always been part of American politics, from the arrival of the Pilgrims through Father Coughlin and all the way into the present day. It is undeniable, however, that this confluence became supercharged with the emergence of the Orwellian-named Moral Majority in the 1980s. Christian conservatives have been a force to be reckoned with in US politics ever since (in case you’ve been in a coma).

But in 2015 and early 2016 there was good reason to wonder if—and why—devout Christians, who in the past had made a ferocious point about the “character” of American politicians (especially Democratic ones) would support Donald Trump. A less likely champion of Christian faith would be hard for a novelist to invent: a thrice married, brazenly philandering greedhead with no discernible religious background, experience, or interest, not to mention his appallingly un-Jesus-like attitudes toward money, Jews, people of color, sexual activity, honest business practices, human decency, and other ostensible hallmarks of the faith. Hypocrisy is an art form within organized religion, but Trump put even those limits to the test.

Accordingly, it took some time for many evangelicals to swear allegiance to Trump—roughly the same amount of time it took for him to secure the Republican nomination. But they eventually flocked to him with a fervor that was astonishing to see, becoming his most reliably loyal and unwavering demographic. Indeed, during the election Trump did far better with that group than many legitimately religious predecessors in Republican politics, including both Bushes and Mitt Romney, to say nothing of Democrats who were devout, lifelong believers like Jimmy Carter, or regular churchgoers like Bill Clinton or Barack Obama.

At the risk of stating the obvious, the zeal for Trump among Christian conservatives (not coincidentally, a group heavily—though by no means exclusively—concentrated in the South) and their almost superhuman ability to rationalize his obvious disconnect with their ostensible faith, suggested that there were other factors in play, such as no-likee-the-blacks. Since taking office that support has not appreciably waned, Trump’s daily tantrums and outrages and what Bob Mueller proves be damned.

So how to make sense of Christian support for Donald “Grab-em-by the-pussy”, “Fine people among the Nazis,” “Putin is a Great Man” Trump?

There is no one better to ask than Bill Jersey.

UNEXPECTED PULPITS

THE KING’S NECKTIE: Let’s start with—

BILL JERSEY: In the beginning. God, that’s always a good start.

TKN: You come to all of this with one of the most interesting backgrounds of anyone I know. You were born in Queens, is that correct?

BJ: I used to say I was born in Yankee Stadium because I didn’t want my kid friends to think I was born in Mother’s Hospital. (laughs) You know, I don’t even know where I was born. Yeah, Jamaica, Queens is sort of where I’m always saying I was born. I think I was.

TKN: What was the church you were raised in? What was the religious tradition?

BJ: Oh, it was a fundamentalist church. And if you said, “What denomination?” they were offended because we were non-denominational. The denominations were all those who distorted the faith, you see. And incidentally, it’s probably true.

TKN: And what were the core beliefs that you were raised in?

BJ: “Jesus said it, I believe it, that settles it.” It was real, real, real simple.

TKN: But who determines what Jesus said? I mean, the Bible is open to interpretation.

BJ: (mock outrage) No it’s not! What do you mean? God gave the Bible to man and told him what to write down. Now, of course, we know that wasn’t what happened at all. In fact, the King James translation was done by an English agnostic, I think. Wasn’t even a Christian. We had a sense of humor about it, though. I’ll never forget at Houghton College—a good Christian school, I mean really good Christian school—we used to say, “If the King James version was good enough for Jesus, it’s good enough for us.”

TKN: Right, that’s the old joke. “If English was good enough for Jesus.” But there was no drinking, no smoking, no dancing….?

BJ: Oh God no. And no swearing. You never said “geez” because that was Jesus. You never said “darn” ‘cause that meant “damn.” Oh no no.

TKN: And did you go to public schools?

BJ: Yeah, oh yeah. Went to public schools because we couldn’t afford anything other than that.

TKN: But did that challenge your religious beliefs?

BJ: No, no, no. I realized we’re of God and “they’re” of the world and you don’t expect them to behave well. You don’t expect them to do anything.

TKN: Did the things that you were taught conflict with the church?

BJ: I’m sure in terms of evolution they did, but I don’t even remember it.

I went to a high school reunion when I was 50 and I said to my classmates—who all seemed to be very old, I was kind if surprised how old they were—I said to my classmates, “So what kind of guy was I? I must have been really obnoxious.” They said, no, you were full of fun. I said, but I never did anything! They said, yeah, we never understood why you wouldn’t go anyplace with us, but you were a fun guy. So I perceived myself as being a major downer in their lives, ‘cause I’m sure I was obliged to convert them, but maybe I didn’t. Maybe that was beginning, that I just didn’t do it.

I know I did find ways of connecting. I bought a little Kodak Brownie camera. Do you remember the little box camera? And I would go to dances and I would take pictures and I would sell them pictures of themselves. So that got me a little money, and got me to be a part of dances that I wasn’t allowed to go to.

TKN: So when did your discomfort with fundamentalism begin?

BJ: I was always uncomfortable with it. I was uncomfortable at being told that if I didn’t save you, you were going to hell. That made me responsible for you going to hell. Now that’s a pisser, man. That is a burden you don’t easily dismiss. So I carried that weight. I would go into New York City with my packet of biblical tracts explaining how you needed to be saved, and I would pass them out dutifully, but somehow when I did it, I just wasn’t sure I was better than the guy I was giving the tract to, or that what it was saying was better than what he might have said if I had asked him. So there always that lingering doubt.

Fortunately, I did meet some really wonderful Christians, in spite of their churches but because of their real faith. Because instead of listening to what their fundamentalist preacher said, they listened to what Jesus said. Jesus actually said a lot of good things. But the Christians I know for the most part don’t seem to remember any of them.

TKN: When you’re talking about handing out tracts in New York, how old were you?

BJ: I was a teenager. Fifteen, sixteen.

TKN: And you’d spent your whole life up to that point in the fundamentalist community?

BJ: Yeah. Even in the Navy, when I was 18, I had a wonderful Jewish friend and he said to me, “Jersey, we’re going out to see some strippers. Why don’t you join us?” I said, “I can’t do that!” I couldn’t do it.

TKN: Now where is this?

BJ: This is on the USS Arkansas, BB33, the oldest battleship in the fleet in 1945. The ship was in the Pacific. By the time I got onboard the war was over, so we were now collecting the still-living or wounded Marines.

TKN: And through this whole period you were still maintaining the faith you were raised in?

BJ: Yeah, I was still maintaining my allegiance to—but discomfort with—my fundamentalist Christianity.

TKN: So what caused the break?

BJ: (long pause) I don’t know. I think it evolved, you know? I don’t know, maybe some people have catastrophic moments or moments of great radical realization. But for me it evolved slowly.

TKN: So not a Damascus experience?

BJ: No, no, no. Paul and I had different experiences with life. (laughs) How do you know all this stuff?

TKN: I had a conventional religious upbringing. Not fundamentalist, but sort of garden variety Protestantism.

BJ: Yeah. So it evolved. And there were people along the way who helped. I was still a Christian at Wheaton College and Houghton College after the Navy, but the shift there was not so much a “denial of” Christianity, but “no need for involvement with.”

So my painting teachers at Wheaton and Houghton were the saints of the world. They were three beautiful people. Two at Houghton College, Amy and Willard Ortlip. They were just the most loving, caring human beings, and boy that was what I needed. And then at Wheaton College, Karl Steele—I wish I knew if he had kids, I would tell them how wonderful their father was. He asked me if I knew how to use a drill. I said, “Use a drill? For a painter? And he said, “Everything you know how to do makes you less dependent on other people.” Now is that Christianity? I don’t know what it is, man, but that’s good advice. (laughs)

The silliness about sexuality, of course, was a great opportunity for me. I’ll never forget at Wheaton I got up and I was gonna sing a song on amateur night, right? So I decided to wear a dress. Now, nobody did that. Not only did I wear a dress but as I sang I scratched my side so I pulled up the dress. And I sang “I Must Go Where the Wild Goose Goes.” And it just brought the house down. So we laughed. And I do remember at Houghton I was in the infirmary, I got a cold I guess, and a young woman came in, absolutely dissolved in tears, she was just desperate. And I asked the nurse, “What happened to her? It must have been awful.” And the nurse said the girl had been kissed and she was afraid she was pregnant. That was the level of sexual sophistication.

TKN: It must have been quite a shock to go from that into the Sixties.

BJ: Well, it was and it wasn’t, because remember, for me in the early Sixties it was still us and “them”—meaning non-believers. And what “they” did which never shocked me, ‘cause that’s what “they” do.

When I made A Time for Burning I was still a good Christian church member and that’s how I got the job from the Lutherans. That’s how I got into the church, how I got the church people to let me film them, because I could sing their songs and quote their Bible.

TKN: I didn’t realize that. I thought you had long before become an agnostic. (NB: A Time for Burning follows a Lutheran minister in Omaha, Nebraska in 1965, fighting to integrate his all-white church over the objections of many of his parishioners.)

BJ: No, no. I got the job because I was a Christian. But as I said, I think my agnosticism existed very early because I just found it hard to believe that all of those nice people in Africa would go to hell just because they hadn’t been told about Jesus. Some of that fundamentalist stuff just didn’t make any sense to me. How would you possibly believe that? That I was responsible for saving every soul I touch? What kind of crap is that? And also all my feelings were terrible, you know, about sex and everything, they were so awful. Seemed it should be awful. But A Time for Burning was a big shift.

TKN: The film itself?

BJ: No. I fell in love with somebody else’s wife on that film. She was my sound lady. And my editor. She was brilliant.

TKN: And she was married?

BJ: Yeah.

TKN: And were you married?

BJ: And I was married. We were both married, yeah. That was 1965.

I have to say in all honesty falling in love with her probably really liberated me. She was Jewish and she was smart and she was loving and she really helped me see the world. I don’t know if my current wife wants this to be said, but this was fifty years ago, and anyhow I don’t care, when you’re 91 you don’t give a damn what anybody thinks about you. (laughs)

And the other, more important thing that changed me was being willing to look for truth outside of my comfort zone.

The church that I was a member of—and technically still am, the United Church of Christ—had a brochure or a column in their magazine called ”Preaching from Unexpected Pulpits.” And it has nothing to do with God or religion but everything to do with your humanity. So “preaching from unexpected pulpits” allowed me to be sensitive to the possibility that truth exists almost everywhere in almost everybody at almost every time. But you have to have a good filter, because people who think they have the truth—I wouldn’t say inevitably but I’ll say with reasonable likelihood—usually don’t. That’s what I’ve found with people in general, and that’s what liberates me from the tyranny of any ideology.

But where I came from is part of who I am. I’ll never forget being on Long island doing a shoot and my filmmaker friends came out to help and they met my family. One friend of mine said to me, in shock, “You didn’t come from them, did you?” And you know what? I did. But whatever your background is, you take that and you use the opportunities it opens up for you. My background opened the door for me to do A Time for Burning. I did a film at Bob Jones University called The Glory and the Power which was another great opportunity. I got hired by Nova to do a film called What About God? All of these terrific opportunities came because of my fundamentalist upbringing.

TWO CORINTHIANS WALK INTO A BAR

TKN: Much has been written about the bizarre devotion to Donald Trump among the vast majority of American evangelicals. But a year into the Trump junta, when this devotion has become taken for granted, it’s easy to forget that it was hardly a foregone conclusion when Trump first entered the Republican primaries.

BJ: Fundamentalist ideologues supporting Trump just drove me up the wall. I don’t think Christian fundamentalists in general connect with their brains too often, but that one really drove me nuts. I don’t want to send this to my sister because I don’t want her to be hurt, but I would love to know if she still thinks that Donald Trump represents the best interests of the evangelicals.

And I make a distinction between fundamentalists and evangelicals. The evangelicals are out trying to save the world, but most of them are not quite literalists. The fundamentalists take the Bible literally. They believe that if God said it, I believe it, and that settles it. That’s what I grew up learning. That really simplifies the struggles of life! (laughs)

And that’s what’s nice about Donald Trump. You’re either wonderful or you’re terrible and it’s not complicated, it’s real simple, you’re thumbs up or you’re thumbs down.

Though it depends on the day. I mean, he likes that Philippine president Duterte now, right? He’ll hate him tomorrow—I hope—but today he likes him, and he wears a shirt that looks like his, and he identifies with him. If he goes to meet with Putin, he’ll like Putin and identify with him. He’s a chameleon. Whatever color you are, if he thinks he can get something from you, he’ll change his colors to accommodate you, and wear your shirt, and smile, and shake your hand, or whatever.

TKN: So this is what I came to ask you, which is the question you just asked: how do you possibly explain an evangelical or fundamentalist or any kind of a religious person’s support for this character who embodies the exact opposite of what their faith professes?

BJ: The exact opposite. Yes. Everything. Having dumped one wife then dumped another wife, and being proud of the pussy that he could acquire because of who he was….

They don’t see it. That is the answer. The answer is that you wear certain kinds of glasses to protect yourself from ultraviolet rays. These evangelicals wear intellectual glasses that protect them from things they don’t want to hear and they don’t want to know.

The fundamentalist churches today, I don’t know what they found in Donald Trump. They certainly couldn’t have thought he believed in Jesus, they certainly couldn’t have thought he was a good teacher of the Bible. You know what I think it is? I think it was simply the defeat of Hilary Clinton, that evil woman, as they saw her. Women should not behave the way Hilary Clinton behaved, if you’re a Christian woman.

As my sister said, “You don’t criticize a man of Gawd.” And you don’t criticize the man who is gonna get rid of this woman who does not behave like a woman should behave, who allows her husband to get away with all sorts of things she shouldn’t have. A good Christian would have left Bill Clinton when she found out about the affair. A good Christian woman wouldn’t try to be President of the United States; she’d be happy to be Secretary of State or Ambassador to Uzbekistan or somewhere, but not President. I think was it was just that Trump was gonna stop the evil.

And that’s what you’ll find in these mega-churches. What they mainly what they sell is stopping the evil in yourself. That’s why you come. You stop the evil in yourself. Jesus said it, I believe it, and that settles it. You don’t have to get complicated. Simplify your view of the world and the blood of Jesus washes you away from all sin so you’re clean.

The part of it that I don’t get is that Jesus said, “Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s and unto the Lord that which is the Lord’s.” I didn’t hear Jesus say, “Go convert the politicians, go run the country.” No: let the politicians run the country. That’s not your job. Your job is to run your life, run your community, witness to the potential faith of Jesus in your life.

I would ask the fundamentalists, “How does that faith alter the way you behave in the world?” Does really believing in Donald Trump make you a happier, more satisfied, more caring person? Make America great again? What a wonderful slogan. It’s too bad he doesn’t believe it.

MISOGYNY AND RACISM, TOGETHER AGAIN

TKN: I would characterize the fundamentalists’ view of Hillary as sheer misogyny, plain and simple. And it’s not limited to fundamentalists. Lots of “mainstream” Republicans had a view that was just as toxic and irrational.

BJ: I remember one film that I did with Sam Keen, we were filming a fundamentalist Christian meeting somewhere and I went up to a woman and I said, “You know, we appreciate you appearing in the film but we need for you to sign a release.” And she said, “Oh, I can’t sign a release.” And I thought, “Oh no.” And she said, “You’ll have to give it to my husband. He’ll sign for me.”

Another time the wife of Dr. Bob Jones, fundamentalist extraordinaire in North Carolina, said to me on camera, (affects Southern accent): “I believe my husband should make decisions for our family because that’s what the Lord wants.” And later I went into her kitchen and on the refrigerator was a sign that said “If Mama ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy.” And I said to myself, “Lady, you got it all right. You says one thing and you does another.” That’s how women survive in the fundamentalist church.

TKN: Right. Because here’s what occurs to me. In A Time for Burning, those religious folks had an animus toward black people….

BJ: Well no, you don’t understand them. The woman said very clearly, “I want God to bless them as much as he blesses me.” Did you hear her say that? That’s not animus. Then she said, “But I just can’t sit in the same room with them.”

TKN: There you have it. This is what I’m saying. It’s like what you said about Hilary. And it’s profoundly depressing.

BJ: But they think they’re protecting themselves against something that would harm them.

TKN: Right. A woman. Or an African-American.

BJ: Exactly.

TKN: That’s the depressing part. Because the core belief that they’re trying to protect is itself retrograde—and that’s being generous—or just plain wrong.

BJ: They’re not trying to protect a belief, they’re trying to protect themselves and their world. When Hitler said the Jews are fucking up our lives, he didn’t want Germany to be hurt by those Jews, who incidentally had done the best work of course in science and technology and everything else.

Once in the Fifties, I heard my father say, “You know, the darkies are really nice people.” To him that was a compliment. He thought “the darkies” were nice people, and calling them “darkies,” well, they were dark so what’s wrong with that? Well, there was something wrong with that, but he didn’t get it.

TKN: So for a person like yourself who came from that world, when you hear something that’s a lie—like, “The Jews are gonna do us harm, we have to stop them,” or “This woman is gonna do us harm, we have to stop her,” or “We can’t let these black people in our church”—how are you able to see through that bullshit?

BJ: I don’t see through it. But I recognize it and put it in films and hope that other people will recognize it, and that if enough people recognize it, fewer people will engage with it. That’s my only hope.

People ask me, how did you get those Christians in A Time for Burning to say that they didn’t want black people in their church? It was because they believed—and it was true—that I wasn’t trying to hang them. I was trying to understand them and let them say who they really were. That’s why I got access at Bob Jones University and places like that. Because I genuinely would like to know what they had to say.

I think you know one of my many lectures is that I’m not interested in the small “t” truth— that’s the facts—I’m interested in the big “T” truth. Being able to see beyond what things appear to be: that’s what I find in religion that is hopeful, but unfortunately the hope doesn’t emerge very often because it’s buried by the fundamentalism.

TKN: Maybe you should make a film about that now, and use your credibility of your background to try to get those present day fundamentalist folks to talk, the way you got those folks in Omaha to talk in 1965.

BJ: I should. Because people always say to me, “What did you intend to do with this film, or with such-and-such?” The only thing I ever intend to do with my paintings, my films, my talks, and even when I just get with my conversations with people on the street, is to try and make them understand that I can hear them, and I just hope they will hear me. That’s all I ask.

O MOON OF ALABAMA

This interview was conducted before the special Senate election in Alabama last month, but the impact of that stunning spectacle—an accused child molester running with the full-throated endorsement of the President of the United States, and of local churchgoers, and the blind-eye support of the RNC—continues to resonate.

As Laurie Goodstein wrote in the New York Times, many Moore voters not only were undeterred by the deluge of credible allegations and evidence against him, but stated that they would vote for him not even if the charges were true. Hypocrisy was the obvious word that leapt to mind, and in world record levels. But even the usual GOP rationalization—that it was crucial to have a hardline right wing Republican in that Senate seat, even if he was a serial sexual predator with a special fondness for underage girls—was a degree of Machiavellianism rarely admitted to by anyone in American politics. As Goodstein reported:

“I don’t know how much these women are getting paid, but I can only believe they’re getting a healthy sum,” said Pastor Earl Wise, a Moore supporter from Millbrook, AL. Wise said he would support Moore even if the allegations were true and the candidate was proved to have sexually molested teenage girls and women. “There ought to be a statute of limitations on this stuff,” Wise said. “How these gals came up with this, I don’t know. They must have had some sweet dreams somewhere down the line.

“Plus,” he added, “there are some 14-year-olds, who, the way they look, could pass for 20.”

When self-described Christians are willing to ignore pedophilia for the sake of suppressing marriage equality, or reproductive choice, or any other of a host of right wing wedge issues (not to mention separation of church and state or the general rule of law), it is fair to ask if religious faith can still be considered the driving force in their cause…..or at the very least, if that religious faith bears any resemblance to what Jesus of Nazareth taught.

******

TKN: Let’s talk a little bit about Roy Moore, speaking of evangelicals. This guy is a hardcore…..I don’t know what the correct term is, in his case. Fundamentalist?

BJ: Oh no, no. He believes he’s a Christian. Oh absolutely.

TKN: I think he’s a perfect example of the distortion of Christianity.

BJ: He is a perfect example.

TKN: Evangelicals in Alabama reportedly are more willing to vote for him now, not less, after the allegations.

BJ: That one’s tricky, but I know why. Because when the devil is opposed to one of your people, even though you might not like those people, you have to go support them. The devil is at work trying to get rid of him.

TKN: Well, I understand his supporters who say, “I believe him and not the women.” I don’t agree with them, but I understand that’s their position. The ones that boggle my mind are the ones who say, “It might be true that he’s a pedophile—I just don’t care.”

BJ: Oh I didn’t hear that.

TKN: There’s quite a few. They’re the people in your example just now of sticking by whomever is fighting on the side of the Lord, as they see it, even if they’re doing terrible things. But when those things they’re doing are so awful, it’s impossible—to me—to accept that they are in fact on the side of this ostensible Lord. By definition.

BJ: Well, what they say is, “Remember, we’re all sinners. We’re all sinners.” So Moore has particular sins that I don’t have, I don’t agree with them, but he’s still our guy. As my mother used to say, “I don’t agree with you, Billy, but you’re my baby.” They say, “I don’t agree with you, Moore, but you’re a Christian.” So that’s what it is.

Embodied in your one question are three questions. Why do they support him in the first place? Because he claims to be a Christian and you have to support your brothers. The man of God has to be supported whether he’s doing bad stuff or not. The second question is why do they support him if they acknowledge that he’s done these terrible things? Even McConnell said he believes the women. But of course I wouldn’t believe anything McConnell says….

TKN: Well, he’s just being pragmatic in that he doesn’t want to lose that Senate seat…..which he may not lose, right? Moore might still win the same way Trump won. But that forgiveness you’re talking about—that idea of “Oh, we’re all sinners”—I don’t see that extended to others. I don’t see it extended to Hilary. I don’t see it extended to Barack.

BJ: No, you’re right, it isn’t extended to them. See, that’s the more interesting question.

TKN: Well, it seems to me like a kind of tribalism or even beyond tribalism.

BJ: Yeah well it’s the most primitive tribalism. I mean these Muslim radicals who go around killing people, and not just Muslim radicals, anti-abortionists like the one in one of my films who said that doctors who perform abortions are baby killers and they should be killed. “Baby killers.”

TKN: I mean you can begin to understand his mentality if you really think about it, but it’s based on a false premise. True, if you kill this one doctor who’s “murdering” a million babies that could be justified by a utilitarian argument. It’s the “murdering a million babies” part that’s not true and therefore that argument falls apart.

BJ: Even if it was true, there’s nothing in the Bible that supports killing another human being.

TKN: So as somebody raised in that same kind of religious community, how did you have a clear vision when so many others didn’t?

BJ: Well I didn’t. (laughs) All I had was what Ingmar Bergman called “through a glass darkly.” It’s the notion that all you have is an uncomfortable awareness that there’s something wrong with what is being pressed upon you. Now, you can do two things with that. Either you can find ways of denying it, and I know people who do that, or when somebody says, “There is an alternative,” then you can scratch away at that smoky mirror and see what you can see. And you’ll begin to see it.

********

Next week, part two of this conversation, in which Bill explains how reading the Bible actually led him away from the church, how his family reacted, the tragically renewed relevance of A Time for Burning, and why religious belief gets a free pass when we assess our politicians.

Photo credits:

Left, portrait of BJ: Lucy Hilmer

Right, still from A Time for Burning: Bill Jersey

Transcription: Sherry Alwell / type916@gmail.com

********

Bill Jersey – Biography

Bill Jersey has been producing groundbreaking documentaries for over 60 years. Since establishing his reputation in the 1960s as one of the pioneers of the cinema verité movement, he has produced films for all of the major networks including a long association with PBS stations such as WNET New York, KCET Los Angeles, KQED San Francisco, and WGBH Boston, among others. Jersey’s body of work includes the award-winning documentaries A Time for Burning and Super Chief: The Life and Legacy of Earl Warren, which were both nominated for Oscars; Children of Violence (about a Chicano family) and Loyalty & Betrayal: The Story of the American Mob, which both won Emmys; The Glory and the Power (about religious fundamentalism); Faces of the Enemy (on the uses of wartime propaganda); and Renaissance (a four-part series on the history of the Renaissance), all of which were nominated for Emmys; and The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow, a four-part series on the Jim Crow era, which won a Peabody. Among this other films are: Fighting Ministers; Crime & Punishment in America; Learning to Fly; Naked to the Bone, Stopwatch, and The Next Big Thing? (all three with Michael Schwarz); The Making of “Amadeus”; Everyday Heroes; Evolution: What About God?; Ending Aids: The Search for a Vaccine; America at a Crossroads: Campus Battleground; and Hunting the Hidden Dimension (for “Nova”). His most recent documentaries are Eames: The Architect & The Painter (about Charles and Ray Eames), which also won a Peabody, and American Reds (a history of the American Communist Party, with Richard Wormser).

A graduate of Wheaton College (with a B.A. in Art) and the University of Southern California (with an M.A. in Cinema), Jersey has been the head of Quest Productions for over fifty years. In 2000 he was awarded the Gold Medal for his body of work from the National Arts Club in New York City. After many years in Berkeley, CA, he and his wife and partner Shirley Kessler are now based in Lambertville, NJ. Jersey is also an accomplished landscape painter whose works have been shown widely in galleries across the US. He is represented by the Lambertville Artists Gallery.

**********

Other relevant articles on this topic:

God’s Plan for Mike Pence (The Atlantic)

After ‘Choosing Donald Trump,’ Is the Evangelical Church in Crisis? (NPR)

Why Evangelicals Are Again Backing a Republican Despite Allegations of Sexual Misconduct (Boston Globe)

Can Evangelicalism Survive Donald Trump and Roy Moore? (The New Yorker)

A Top Church of England Bishop Scolds U.S. Evangelicals for ‘Uncritical’ Support of Trump (The Washington Post)

Frank Schaeffer Explodes at the GOP

Excellent. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Robert. I appreciate you reading and glad it resonated with you…..

LikeLike

Great stuff! Have enjoyed the arc of this conversation, beginning with the James Carroll interview.

LikeLike

Thanks Dave! Part 2 coming this week, with more on this same topic…..

LikeLike

Fascinating! I feel like I was there for the interview. But now I wish I actually was there and part of the conversation. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you Mary Beth! I appreciate your kind thoughts and I’m glad you enjoyed the interview. Check out part two: https://thekingsnecktie.com/2018/01/10/truth-or-consequences-bill-jersey-on-the-end-of-evangelicalism-part-2/

LikeLike