As a middle-aged, middle class white guy, my thoughts on race in America are not exactly in great demand. So I wanted to speak this week with someone whose perspective was far more direct and visceral.

As a middle-aged, middle class white guy, my thoughts on race in America are not exactly in great demand. So I wanted to speak this week with someone whose perspective was far more direct and visceral.

Faith Duggan—a native New Yorker and 19-year-old rising sophomore at Clark University in Massachusetts—is two things I decidedly am not:

Young and Black.

I’ve known Faith and her sister Isabella since birth. For our conversation, Faith was joined by her mother, Odette Duggan, who is field support liaison for the New York City Department of Education, with a background in pluralism, diversity, and education management, and who has been one of my wife Ferne’s closest friends since college. (I say this not to “Hey, I have Black friends!” but only in the interest of context and full disclosure.)

The Duggan family touches on numerous, complex aspects of race in America. Odette was raised by a single mother who came from the Dominican Republic in the early Sixties. Her mother, Diana Cabrera, was a medical technician at Mount Sinai Hospital and worked tirelessly to send her to Nightingale-Bamford School, one of Manhattan’s most elite all-girls private schools, where Odette was one of only three Black students in her class. She graduated in 1983 and went on to USC (which she will tell you is another bastion of whiteness), graduating in 1987, and subsequently earned her masters degree from Hunter College.

Both of Odette’s daughters followed her to Nightingale, where they were the school’s first legacies of color. But the deep-seated white privilege of an Upper East Side private school has barely budged in the intervening years, or even now, as the country is roiled by a reckoning with 400 years of institutionalized racial oppression.

We spoke by Zoom about that legacy, the current Uprising, George Floyd, Amy Cooper, and the complexity of race in the USA. It was an apropos conversation for a week that saw the President of the United States approvingly retweet a video of two of his supporters shouting “White Power!” while riding in a golf cart past anti-racist protestors.

AMYS AND KARENS AND GEORGES

THE KING’S NECKTIE: Let’s just start with something specific, Faith. Where you surprised by the public reaction to George Floyd’s murder?

FAITH: I wasn’t expecting anything different because Eric Garner got killed in 2014, when I was 13 years old, and now six years later I’m 19 and nothing’s really changed. So I wasn’t expecting much. It seems like over the course of history, even when things do change, nothing’s really going to change.

The reaction is bigger because of social media. We’re all stuck inside with covid, everyone is at home and everyone saw it. You have nothing to do but watch the news and stare at your phone, so everyone had time to read the paper and see every article about it, and they’re like, “Oh shit, I’m not immune to this.”

TKN: It’s super ironic that on the same day as George Floyd’s murder there was the Amy Cooper incident. As a New Yorker, what was your reaction to that?

FAITH: I didn’t understand her motives, but just as a human being, I was like, use some common sense. He’s recording you. He’s a birdwatcher, and you’re going to call the police on him for being too black? You’re calling the cops and reporting a crime that did not occur, which is an illegal offense on its own? For me, that was more like an indictment of her as a stupid person rather than as a white person.

ODETTE: I completely disagree. I think that’s a perfect example of ageism. (re Faith) She doesn’t have the depth of knowledge to see the maliciousness and to know that that woman knew full well that even though he was this guy from Harvard, she could still make it sound like he was threatening. Every time I talk to people, I tell them, “I can’t have this conversation about race until you realize that George Floyd and Amy Cooper are married.”

TKN: Right. The whole reason she made that threat, to call the cops, is because she knows how it plays out.

ODETTE: Right. She knows the police come, cuff him, put him face down, and ask questions later. To me, Amy Cooper has to be spoken about when you speak about racism in America.

Most people have been taught that it’s impolite to discuss race, and I think this is one of our big problems. We are not skilled at discussing racism.

In order to solve the problem of racism, humans need to understand that they’ve got implicit bias. And white people, even if you give to good charities and you gave money to send the poor little Black kid to camp, you still have it in you. That doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. People believe that only bad people are racist, and that actually makes matters worse, because it prevents people from looking inward at themselves. But this country raises you from the beginning with the messages on how to behave when you feel threatened. Look at the science experiments with the black dolls and the white dolls. So that tells you that by two to three years old, children have seen enough—either through their family, in their communities, or in the things they’re reading or watching—to understand what is deemed good and bad according to the rules of society.

TKN: I’ve got a friend who talks about how white children, from birth, are confronted by people of color in subordinate positions, and not so much in positions of power. So they can see society’s pecking order and internalize it before they can even speak or understand it, let alone have to be told or taught.

ODETTE: I remember it happened to James Blake, the professional tennis player, in front of the Grand Hyatt Hotel. They were looking for a suspect, he had just come out of Grand Central, he was here for the US Open or something, and they had him on the sidewalk, face down, until they realized that he wasn’t a criminal, he was this elite professional tennis player. People were shocked. But I was like, that happens all the time!

TKN: And like Christian Cooper, James Blake is another Harvard man. Maybe these cops all went to Yale.

ODETTE: That’s why so many people got so mad at Obama when he said about Trayvon Martin, “That could have been my son, or me 35 years ago.” White people were appalled. “How could you have said that?” I was like, because it’s a fact. Obama wasn’t trying to say, “Oh, you know, I’m with my brown posse.” No. It was literally just a fact. It could have been him, or his son, or his daughter.

FAITH AND HOPE

FAITH: I think it hit me that this moment, the reaction to George Floyd’s murder, was different when it reached the private schools. That’s where I spent 13 years of my life, in them and surrounded by them and the product of them. So when it hit those schools, and there was…..not change, but momentum and the possibility of change, that’s when I got a little more hopeful.

There are all these Instagram pages now, BlackatNightingale, BlackatBrearley, and all the other private schools in the city. So having that, and having every single one of my friends know about it from all around the five boroughs, it was kind of like, it might not change the outer world, but it’s going to make some change in my academic community. Because if the same things happened to me that happened to my mom thirty years before at the same school—maybe even worse because there are more kids of color for it to happen to now, and more silence—how am I supposed to expect change, let alone hope for it?

TKN: What kind of things are you talking about?

FAITH: Racist things. Macro and micro aggressions. Nightingale as an institution shutting up kids of color when they don’t want to hear it. Like, “It doesn’t help our agenda, so we’re just going to sideline you. You can be on our calendars, or on our brochures—if you’re dark enough—but you can’t actually make a change within the school.”

Nightingale has specific kids of color that they want to reuse over and over again. Personally, I was never dark enough. I was too outspoken. I was too this or that…..so I wasn’t good enough for Nightingale to abuse. How is it fair that students of color who have attended the school for ten minutes are asked to escort potential students, or speak on panels for incoming POCs, when I was never asked?

TKN: Odette, having gone through that same school, and now as a parent of one child who’s a graduate and of another who’s still there, what’s your perspective? Have there been any changes, or has it just gotten worse?

ODETTE: I think it’s gotten worse. There was always money when I was there in the Seventies and Eighties, but now those that have money have much more money, and it’s newer money, and it’s more in your face. We didn’t know that the daughter of the head of the World Bank was in my class, because it wasn’t something people talked about. Now everyone kind of wears their resume on their sleeve. And the dynamic of the school appearing to do what is best for kids has kind of gone away with trying to make sure its endowment is continuously fed.

FAITH: The divide was always there between the black and white communities, but now it’s larger, and there are more kids of color and they’re living in the Bronx or in Brooklyn, and not living seven blocks away from the school.

ODETTE: The truth of the matter is they don’t need to have kids of color at that school. The school doesn’t need the money. They just need to look like they’ve checked all the boxes, they don’t have to believe what’s in the boxes, or need to do the actual work towards accomplishing those things, like creating meaningful relationships, empowering the kids to challenge the status quo, and to advance equity for the betterment of all. The school just needs to be able to say like 20% or 30% of our students are of color, and then 80% of our students are on financial aid—some form of financial aid. They have to have that image, so a parent can feel good about spending $55,000 to send their daughter there, and feel good about themselves.

FAITH: Racism has been happening right beneath Nightingale’s nose, and they were told about it every time, but they just don’t care.

ODETTE: Having been associated with Nightingale for over 35 years, I know that the school is vengeful. I don’t trust them. I’ve seen what they’ve done. I spoke out and they took my post away as head of the Parents of Daughters of Color, which I’d been for five years.

TKN: How did that happen?

ODETTE: Faith had gotten into the NYU STEM program, but she would have to miss a couple softball practices and maybe a couple of games. And I was told she couldn’t do it and stay on the team. So I wrote to the head of the school and the head of the upper school and asked, “Are we so serious about sports now—especially softball—that we force young adults to choose between their futures and being an athlete?”

Then I was contacted by the head the athletic department, who was brand new, who told me that Faith was in fact going to have to choose. I said, “Are you kidding? Are we an athletic school? This team has never won, since she was in fifth grade.” And that’s not even the point. The point is, this program is offering her something of value, and it comes with SAT prep worth $7000 that I can’t afford to give her.

FAITH: There were a couple other people on the softball team and the lacrosse team who were also juggling other things, or musical theater or whatever, and they would have missed the same amount of practices and games, which was roughly five. And they all got excused. I was the only one who didn’t.

ODETTE: So I had a meeting the next day with the head of school, and he said, “The head of athletics told us that you threatened her and hung up on her.” I was like, are you kidding me? I went to this school. I was the head of the alumni board for five years. I was on your board of directors. But this person who’s been in the building for three months, you believe her? So we’re speaking and I’m telling him what I’m feeling, and he says, “Please watch your tone.” And I said, “Excuse me, have you not heard this tone before? This is frustration. This is anger. This is sadness. This is a lot of things, but it’s not disrespectful.”

TKN: That’s the “angry black woman” allegation, right? You’re telling me that the head of a fancy all-girls private school has never had to deal with an irate parent?

ODETTE: Yeah. That was in February or March of last year. Then around June I got a note from the head of school saying “We’re going in a different direction” with the Parents of Daughters of Color and it’s going to be run by Ms. So-and-So, a member of their staff. Who’s not married. Doesn’t have a child. This staff person is going to be running the Parents of Daughters of Color? Okay.

I just found it interesting that they had someone who’s been associated with the school for 35 years, an alum and an active parent, but they chose to believe the white woman who’s been associated with the school for just three months. You don’t think that’s a black/white issue?

Look, I love my school. I was a Nightingale girl. I was there for 11 years, 2nd grade to 12th grade. Whatever happened to me there made me the person that I am, and I’m very happy with who I am. So when I challenge Nightingale, it’s not because I think my girls will benefit, because they’ve already been injured and hurt. But I want the kids coming after them to have a better experience.

TKN: Did you understand that when you were going there, or did you develop that later?

ODETTE: No. It was an adulthood realization. You don’t think about that when you’re there, because you’re a teenager. I was thinking about my friends, boys….I was barely even thinking about school. I was lucky that I was able to develop my personality in a way that kind of protected me from long term injury. But not everybody figured out early on what they needed to do in order to survive. Some people take longer to figure that out.

I don’t dislike my school. I just want them to do better. I want them to allow children who look like me—brown, Black, Asian—to succeed. If you’re going to allow them at the table, feed them. Let’s use George Floyd: get your knee off their neck. Don’t invite them in and then shut them down so that they come out of there not whole and with a psychosis, because they’re not as rich as their fellow students, or they don’t go to the country or they vacation at home, or spend their vacation working. They shouldn’t feel guilty that they have to work.

You have to understand the amount of hours I’ve given to that school. I was the president of the alumni board for six years. I was on the board of directors. I’ve been the reunion chair every year we have a reunion. It would be different if I didn’t want to be part of the solution and I was just bitching. But I want the school to be better because I went there and my name is associated with it. There’s no joy in knowing that your school is under indictment and everyone hates it. I want my girls to be happy to say they went there, and not just whisper it under their breath.

WHITEWASHED

TKN: I know you’ve been on distance learning lately, Faith, but what’s the feeling at Clark? Is it similar or different?

FAITH: It’s different because Nightingale was so much smaller. But since Clark is so much bigger, people of color stick with each other. We’re maybe a hundred or two hundred people out of 2000, so you don’t mix with the white students a lot. So I have an Asian friend who was adopted by two white parents, so she’s also kind of a little whitewashed. And then I have a Latino friend who also went to a prep school in LA, who’s also a bit whitewashed. And then I have my friend who actually went to Brearley in the city and we graduated the same year and she’s Black and she’s not as whitewashed as I am. So that’s nice.

But it’s so different when you’re light-skinned and no one can really tell that you’re a person of color and you’ve been whitewashed. You don’t listen to the same kind of music, you don’t dress the same, you don’t talk the same, you don’t have the same life experiences…..It’s harder to connect.

TKN: Give me your textbook definition of “whitewashed.”

FAITH: It’s when you’ve been in an all-white world. It can be whitewashed or code switching, depending on your experience. If I had a more “black” experience that was separate from Nightingale, I would just codeswitch between the two. However, since I don’t have that, I’m just whitewashed.

ODETTE: But then she had experiences that were majority minority. Like I got her into that STEM program and it didn’t work out because she wasn’t seen as black enough and was too academically privileged.

FAITH: Right. So I got into the program, because I fit all the requirements, but when it got to the third section of the program, which would have been writing your college applications, they’re like, “We’re going to ask you to leave because you don’t need our resources.” And so the people of color that I could have built relationships with were kind of pulled away from me. I was there for four weeks and then they were like, “You can go now, you’re not Black enough for this program, basically.”

Then I went to the Schomburg Center’s Junior Scholars program, which was a group for all Black kids, and we were learning about Black history in the first half of junior year, and in the second half we did art-based projects. There was theater, there was writing, there was poetry, and I was in the comic book section and I loved it.

But when I went back for senior year, and it was another year of Trump and everyone was kind of hardened until it was like, if you don’t look like me, if you’re not dark enough, you don’t fit in here. And I got berated every day for passing because I didn’t have the same experiences. And I’m like, “You’re right. We don’t have the same experiences. However, I do experience different types of racism and colorism because I’m not Black enough and I’m not white enough. I’m just in the middle. In this binary world you get to be one or the other.”

A CHANGE IS GONNA COME (MAYBE)

TKN: So, I don’t want to sound stupid, but do you think there is any chance there will be substantive change as a result of this post-George Floyd Uprising?

FAITH: I feel like maybe there will be change, but maybe the change will be slow and tiring and painful. It’s not going to be a quick change where (snaps fingers), “Okay, we’re done.” No. We have to systematically uproot our current system. We have to rip everything out of our institutions, we have to change our mentality that Black is bad, Black is dark, Black is evil. We have to change our DNA.

ODETTE: The sad truth of it is that until it hurts white America’s pocketbook, change is going to be ridiculously slow. Cause “I got mine.” Right? People who fled the pandemic are moving their kids from schools in Manhattan to schools in the Hamptons. “I’m not really worried about the pandemic. I’m just going to move somewhere else.“ So it’s gotta be an economic thing.

It’s good that we’re beginning to deal with it on the police front, but the one thing that white America still hasn’t done is realize that they have been trained to be racist, to have an implicit bias. Do you have any Black friends? Most of white America does not.

I remember visiting my friend in Choteau, Montana and I swear, I gave this old woman a cardiac arrest. (laughs) It was clear she’d only seen Black people on the boob tube. We were going into the IGA, and it took her like at least a minute to try to close her mouth. I’m sure she wanted to touch me or something. But the look on her face!

And that’s most of America. Most of America doesn’t have a good friend that’s Black. Their children might go to school with brown people, but they’re not having them over to dinner. They’re not finding common ground. So it’s easy to just believe the bullshit, because they have no other point of reference.

And that goes to the point of educational curricula. If all we teach is slavery, that’s all people relate to. If you look at these “Black@whatever independent school” Instagram feeds, a lot of them have stories of white students saying to their Black classmates, “You’re brown, you can be my slave.” That’s a common thing in elementary school. They’ve heard about Miss Jane Pittman, they’ve heard about slavery, and they realize if you’re brown, you must be a slave. I know we need to teach the history of slavery, but that can’t be all we teach.

FAITH: Here’s one from the class of 2009. (reading Instagram post) “In third grade, a student from the grade below me grabbed my unbelted tunic belt and said, ‘Giddy up slave. You’re black. That makes you my slave.’”

ODETTE: When I was a kid, I had to call my friend’s house under a different name because they knew “Odette” was Black. So I had to call Scott’s house and say I was “Mary.” And in his yearbook he wrote, “Thanks Mary.”

When I started Nightingale, we lived in Washington Heights, 157th Street and Riverside Drive. When I was in sixth grade we moved into our apartment on 93rd Street between Second and Third, and there was nothing north of there—it was just empty lots. That’s where we went sledding, before they built all those high rises. It scared people. My friends had to beg their families, “Can I go over to Odette’s? She lives on 93rd Street.” (gasp!) “Oh my God.” But they grew out of it later, because all the parties were at my house.

But then there were parties I wasn’t invited to, and the part that hurt was that my friends wouldn’t tell me. Like, we’re not close enough for you to just say, “My parents are dicks, they won’t let me invite you, I’m so sorry?” You just thought I wouldn’t find out? But when you ran away from boarding school, where did you stay? Odette’s house. So you trust me enough to keep you covered so your parents don’t hear when you run away from school, but you can’t invite me to your party?

There was only one other Black student in my class most of my time there and what was happening in her household was very different than mine. Her experience and her culture were African-American; mine was Dominican. We were a traditional Latina household where we had dinner between eight and nine, the TV always was on with the Spanish soap operas, we weren’t eating collard greens, we were eating rice and beans and plantains. We had totally different experiences. I was raised with my own prejudices. So I had to deprogram myself. I do a lot of work to try to keep my mind open. But I had to practice that. That was a skill I had to build up.

It’s something I tell everyone: Being able to talk about race is a skill. And if you don’t work at it, you don’t build up that skill.

TKN: I mean, it’s interesting that you’re talking about asking white people to do the least they could possibly do, which is to admit, “Yeah, there’s a problem.” And it is hard to get them—us—to do even that. I got angry pushback last week from people I know who argued that there is no systemic racism, just a few bad apples on some police forces—the standard dodge. If white folks can’t even accept that there’s a problem, then we’ve really got a problem.

ODETTE: That’s the bare minimum. So if they can’t do that, then somehow Black people have to be able to hit them economically. And I don’t think we’re united enough—I know we’re not united enough—to do that. The systemic racism is so deep that it’s hard to convince people of color, “Don’t buy from that place. Buy it from the place who’s owned by a Black man or Black woman.” But we don’t have that communication system, because of the varied experience people of color have.

TRUMP AS CORRECTIVE

(My wife, Ferne Pearlstein, who became friends with Odette when they were in their twenties, joined the conversation.)

FERNE: I have a question about what you were saying earlier about the perfect storm. It pains me even to suggest it, but do you think we could have gotten here, to this point where there’s at least the potential for real change, if there had been no Trump? Did our country have to sink this low before we could begin to fix things?

FAITH: I think we needed the polar opposite of Obama to get here. Because if not, we would have just been skimming the surface. (sarcastic) “We had a Black president! There might be racism in the South, but not here in the North. We’re liberals, we’re Democrats!”

People use this excuse of “How could we be a racist country? We had a Black president!” And I’m like, “OK, then having Trump shows we are racist.”

ODETTE: I feel like it was coming anyway. When I worked for the Girl Scouts, we were doing all this market research on how to reach out to underrepresented populations, and the media started catching on to the projections that by 2030 America is going to be “majority minority.” The value of the Latino dollar and African-American dollar, how much buying power they were going to have. Because again, it’s about money, and once the whites are outnumbered, their fear of what they’re losing, I think we were doomed to have some kind of clash. If it wasn’t Trump, it would have been something else. But he’s helped us along.

TKN: The question is interesting: “Would we have gotten here if it wasn’t for Trump?” The fact that we got him is the answer to the question. The reality of a Black president scared so many white people, that the pendulum went swinging the other way. It was inevitable that Trump, or somebody like him, was coming.

ODETTE: An over-correction. Not that Trump is a “correction” to anything, but yeah. White people were mad. They felt threatened. “What? Majority minority?” Then you got this Black guy in the office. “What the hell?!”

TKN: To me, the birtherism is the classic part. Because they were desperate for a reason why Obama couldn’t really be president. And they ended up with the most ridiculous reason. That was the depths of their desperation.

ODETTE: That goes back to how bad our education system is. Because if you’re not educating your kids, they can’t push back at their parents to change their thinking. It doesn’t necessarily help African-Americans, though, because at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter that I have a PhD or this or that, because they’re just going to shoot me at the site of my brownness. But if you can at least educate white people so they’re not just being fed a bunch of Fox News lies, they’d be able to discern what is truth and what is fiction, and perhaps the match wouldn’t have lit so quickly.

TKN: But that’s exactly what the Republicans don’t want. They want to keep white people divided from people of color. As a force for dividing people, in America, race is stronger than class, and economic interests, for sure.

ODETTE: It is. Because you can just lead them by the nose.

********

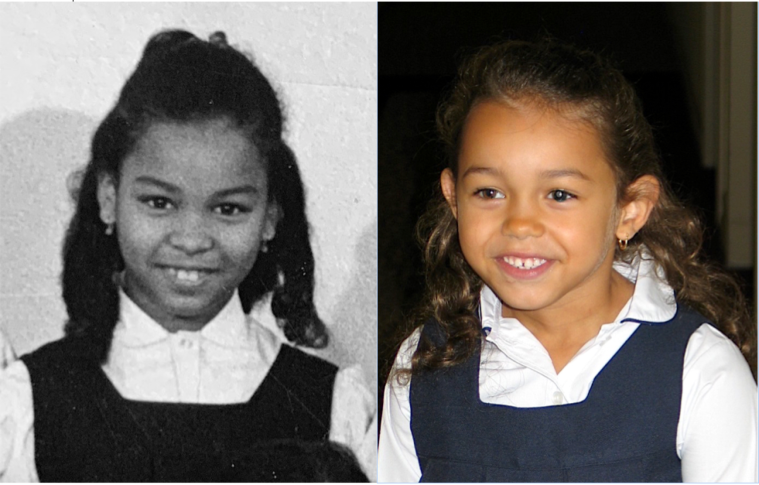

Photos courtesy of Odette Duggan. Odette in 2nd grade, 1973; Faith in kindergarten, 2006.

Wow–that was fantastic to read. There is so much just not experienced or taught or told in this country. We hide in our little corners and end up super shocked at everything that happens. I hope like hell we don’t crawl right back into our holes again and board them up. We live in a diverse country, but know nothing about each other and don’t even try if it can’t be categorized or easily referenced. Ugh. We’ve gotta do better at reaching out and meeting other people in the middle, get to know them, and hit the wallets of the complacent jerks.

It’s like this mask thing: so much selfishness going on. Don’t people realize they could be harming other people by not doing some basic protective measures, by keeping other folks in mind? Nope–it’s all me, me, me. It physically hurts me deep down that people can be so blatantly crass and I have to be around them a lot for my job. I don’t mind my job–it’s not super complicated (most of the time) and keeps me busy, but man… the more people I come in contact with, and the more odd things get with regulations and such, the more worried I get about going to work because you know there are folks beyond the walls that they’ve interacted with who don’t give a hang about others. And probably a third haven’t covered their nose with said mas, either, which is frustrating and dismaying all at once.

LikeLike

This was really great! I would love to meet Odette and Faith and talk about being people of color in the private school sector. Thanks, Bob, Odette, Faith and Ferne!

LikeLike

Impressed with the open dialogue about race. It’s not an easy topic to swim in without defensiveness, guilt, and blame muddying the waters. Thanks for the clarity!

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and for your kind comment!

LikeLike